Sat 28 May 2022

Painting by the Numbers: An exploration into evolutionary algorithms

In a recent second year University project, I was tasked with developing an evolutionary algorithm for reproducing images using a limited number of semi-transparent polygons. I spent so much time above and beyond what I needed to that I thought it was worth writing a post about how I went about my work and challenges along the way.

What are evolutionary algorithms?

The basic premise of an evolutionary algorithm is: you have a population of solutions; this population goes through some sort of mutation, reproduction, or mating; the individuals in the population are then evaluated according to a particular fitness function and the fittest survive. The idea with evolutionary algorithms, as with evolution of biological species, is that given sufficient time, variation, and evolutionary pressure, it is possible for individuals to emerge that solve the particular problem you have placed upon it.

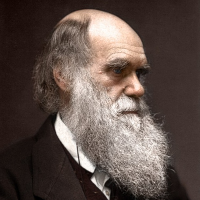

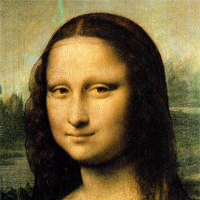

Just as when faced with the problem of getting food from land, some fish became amphibious, and eventually exclusively land creatures. Given the problem of wanting to look like the Mona Lisa, a population of shapes will emerge that solve this problem.

The brief

The brief was inspired by Roger Alsing's blog post where he did a similar thing. His algorithm was quite simplistic in what sort of mutations it offered and it was therefore felt we could make some improvement on this.

The final submission for the project was written in Python using the DEAP library, however, I fancied a speed-up. And using a compiled solution like PyPy was not cooperative and so I rewrote the program in Go. Because of various hoops and hurdles in releasing University coursework submissions, the original python implementation is not available. My Go rewrite, however, is available at my GitHub. I am not as experienced in developing in Go as with python but I feel I have made (mostly) sane, if not idiomatic, choices.

The Program

Making the population

var individuals []Individual

for i := 0; i < 256; i++ {

individuals = append(individuals, makeIndividual(MAX_POLYGONS))

}

I start off by making the population of Individuals. In this case I make 256 individuals with each individual consisting of 100 polygons.

Our Polygon and Point structs looks like this:

type Polygon struct {

color rgba

vertices []Point

}

type Point struct {

x float64

y float64

}

To make a polygon I simply create instances of these classes with various random starting values in order to provide a diverse population from which a solution can emerge.

func makePolygon() Polygon {

// Create colour

polygon := Polygon{color: rgba{

r: uint8(rand.Intn(255)),

g: uint8(rand.Intn(255)),

b: uint8(rand.Intn(255)),

a: uint8(rand.Intn(255-75) + 75),

}}

sides := 3

// Create vertices

for i := 0; i < sides; i++ {

x := rand.Intn(200)

y := rand.Intn(200)

polygon.vertices = append(polygon.vertices, Point{x: float64(x), y: float64(y)})

}

// Arrange vertices such that they don't create a shape that self intersects if a polygon has more than 3 initial sides

polygon.removeSelfIntersect()

return polygon

}

See This section for more details on how I made sure polygons didn't self-intersect.

The polygons then go on to form an individual:

func makeIndividual(n int) Individual {

var polygons []Polygon

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

polygons = append(polygons, makePolygon())

}

ind := Individual{

elements: polygons,

fitness: -1,

}

return ind

}

Individuals are initialised with a fitness of -1, which means that fitness is invalid and needs to be re-calculated. In order to prevent doing more processing than necessary, I will reset the fitness back to -1 whenever a change is made to that individuals polygons. Doing this means that I can guarantee that if a fitness is not -1, the polygons haven't change and I can skip that individual's evaluation.

Generating offspring

Every generation, new offspring are created from our current population. The strategy I went with (varOr) leads to each child being either a copy of a parent, a mutation of a parent, or a mating between two parents.

for i := 0; i < generations; i++ {

offspring := varOr(population, 120, 0.25, 0.4)

// ...

}

Mating involves getting a taking a random point in the list of polygons as a pivot point, then swapping everything after the pivot point with the same set of points from the other parent. Leaving a child where the first half(ish) of the polygons are from one parent, and the other half(ish) are from the second parent. Any children from this process are also given an initial fitness of -1, as the parent fitness is no longer valid due to half the polygons being different.

// Get pivot

cxpoint := rand.Intn(size-2) + 1

// Swap ends

temp := ind1[cxpoint:]

ind1 = append(ind1[:cxpoint], ind2[cxpoint:]...)

ind2 = append(ind2[:cxpoint], temp...)

// return children

return ind1, ind2

Reproduction involves a simple copying of one individual across generations, as such the fitness does not have to be invalidated to -1 because it is a perfect copy of an Individual with valid fitness.

// Choose individual

idx := rand.Intn(len(population))

// Clone individual's polygons

ind := clonePolygonSlice(&population[idx].elements)

// Add new individual with same polygons to offspring

offspring = append(offspring, Individual{elements: ind, fitness: population[idx].fitness})

Mutation is where a large amount of the uniqueness of this implementation comes in, and where a lot of the improvement was made during development. The following mutations can occur to an individual:

- Change colour of polygon

- Change transparency of polygon

- Add a polygon to an individual (within 100 limits)

- Remove polygon from an individual (within 20-100 limits)

- Add a point to a polygon (requires removing self intersect)

- Re-order how polygons are stacked

- Change position of a single point

- Change position of all points at once

The mutations were picked through a process of 1% inspiration, 99% calculation. With many trial and error runs of various mutations and algorithm choices before settling on the current set with their current probabilities of occurrence.

Offspring evaluation

Once we've got our children, we need to see how good they are. It is at this point that Go slightly comes into its own. Evolutionary algorithms, particularly the evaluation, are incredibly well suited to multithreading. Each evaluation is entirely independent and, as such, each one can run in its own thread, speeding up things significantly on multi-core systems.

It is also in this aspect where Go also comes into its own, as Go has first-class support for multithreading.

If you have a thread-safe function, then spinning it up in a new thread is as easy as putting the keyword go before it.

var waitGroup sync.WaitGroup

for offIdx := 0; offIdx < len(offspring); offIdx++ {

if offspring[offIdx].fitness == -1 {

waitGroup.Add(1)

go func(offIdx int) {

defer waitGroup.Done()

offspring[offIdx].fitness = evaluate(offspring[offIdx].elements)

}(offIdx)

}

}

waitGroup.Wait()

In this instance, we loop through all the offspring, and if the fitness is invalid (like it is the result of a mutation or mating) we evaluate the fitness of the Individuals polygons.

All the WaitGroup stuff around it just holds a counter of how many routines are left to finish until we can carry on with the program.

This allows us to utilise all the physical cores on our machine during the evaluation stage.

The evaluation itself is quite straightforward. We draw the individual out onto a canvas, convert it and the target image into greyscale, and then go pixel by pixel to calculate how different the image is. The individual with the smallest difference between its greyscale and the target greyscale is determined to have the highest fitness.

func evaluate(solution []Polygon) float64 {

img := drawSolution(solution)

diff := ImageDifference(img.Image(), TARGET)

MAX := float64(math.MaxUint16 * img.Height() * img.Width())

return (MAX - diff) / MAX

}

Offspring selection

After we have our children, we must pit them against each other to the death. The selection method I chose was tournament selection, this works be getting a random sample from the population and carrying the best from that sample into the future generation.

func TournSel(individuals []Individual, k int, tournsize int) []Individual {

var chosen []Individual

for i := 0; i < k; i++ {

var aspirant []Individual

for j := 0; j < tournsize; j++ {

aspirant = append(aspirant, individuals[rand.Intn(len(individuals))])

}

chosen = append(chosen, BestSel(aspirant))

}

return chosen

}

I then draw out the best child each generation just so I can see the progress as it goes on. Apart from that, our generation is over and the cycle starts over again.

The results

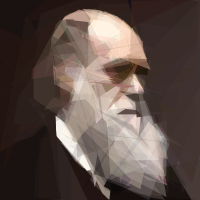

Even though we never do anything other than random, indiscriminate changes, after about 250,000 generations we can get pretty good images made up of very few polygons.

Appendix

Non self-intersecting polygons

When it comes to the vertices of a polygon, you can't just start drawing lines between them and hope for the best.

If I have 4 points that are going to make up my square:

And then I start drawing lines between the points in any order:

That ain't no square chief. So, how can we tell which order we should connect the points? One way to do it is with the power of vectors and angles. First we start out with a base vector, which we just use to be the vector between the center of the polygon and the first point:

We then get vectors between the center and each point in the shape:

If we then get the angle between the base vector and all of those vectors, we notice a pattern:

The order in which we wan't to connect the dots in, also make increasingly large angles with the base vector. Therefore, if we get our points and sort them by the angle their vector makes with the base vector, they will be in the order in which we can draw them.

The code for the mathematics itself can be found in polygon.go